The London Concours has raised the green flag, signalling the start of one of the most high-octane displays at this year’s London Concours: the ‘Great British Racing’ class.

Assembled in the grounds of the Honourable Artillery Company will be many of the automotive stars that tell the proud story of British race engineering – cars that brought home trophies and wowed the crowds at circuits the world over. From the heady days of 1970s Formula 1, through the thrills of rally and Touring Car racing, to the high-power, high-tech engineering of the late Eighties, the London Concours will chart the development of this country’s motorsport story from the 1960s to the present day.

Marking this year’s 60th anniversary of John Surtees becoming Formula 1 World Champion, the Great British Racing class is proud to display the TS9 car he designed and which bore his name. The 1971 Surtees TS9B with its distinctive angular design is powered by a 3.0-litre V8 Ford Cosworth DFV (standing for ‘double four valve’), said to produce 450bhp at a heady 10,800rpm. It first saw action in the 1971 British Grand Prix at Silverstone with Derek Bell at the wheel, before Surtees drove it to victory in the Gold Cup at Oulton Park later that year. The following month, Mike Hailwood crossed the line in fourth place at the Italian Grand Prix at Monza, while Andrea de Adamich achieved a similar placing in the Spanish Grand Prix at Jarama the next year.

The class will also feature a Formula 1 car with a rather distinctive, very ‘70s, livery: the Penthouse sponsored Hesketh 308E. Designed by Frank Derne and Nigel Stroud, the 308E was powered by one of the greatest racing engines of the era; the Cosworth DFV 3.0-litre V8 allied to a Hewland FGA400 five-speed gearbox. It debuted at the 1977 Race of Champions at Brands Hatch where it finished ninth driven by Rupert Keegan who, despite qualifying for every race entered that season, managed only a seventh-place best when he raced it at the Austrian Grand Prix. However, it was the racy livery of the Hesketh’s sponsors that captured most attention, depicting a ‘Penthouse Pet’ from the popular men’s magazine, cuddling a packet of Rizla cigarette papers.

When Rover predecessor British Leyland approached Williams Grand Prix Engineering to build a machine for the Group B rally series, the Metro 6R4 was the rather astonishing result. Williams turned the diminutive ‘shopping’ car into a snarling, mid-engined, four-wheel-drive monster that could rocket to 60mph from a standstill in a fraction over three seconds. Shoe-horned into the tiny shell was a specially built 3.0-litre, double-overhead-cam V6 that, unlike its competitors’ engines, wasn’t turbocharged yet still managed to generate 410bhp in top specification. Tony Pond was at the wheel for the 6R4’s debut at the 1985 Lombard RAC Rally, where the car finished third overall, going on to win the Circuit of Ireland driven by David Llewellin the following year. More victories followed, before safety concerns signalled the end of the road for Group B rallying.

“Simplify, then add lightness” was the mantra of Colin Chapman, whose philosophy was embodied in a series of innovative road and race cars, such as the 1962 Lotus Elite in the Great British Racing collection. The Elite’s lightweight glassfibre monocoque construction was also very strong, supporting all the mechanical components, including its featherweight, overhead-cam Coventry Climax engine that squeezed 75bhp from just 1,220cc. The Lotus was streamlined, too, with a drag coefficient of just 0.29, all of which saw an Elite entered by Team Lotus and driven by Jim Clark finish first in class and eighth overall in the 1959 Le Mans 24 Hours, at an average speed of 94mph. Built to a similar specification, the Elite on show competed in events across the US, where it became well known for the racoon tail hung on its bootlid by driver Bob Challman.

Ford’s Mk1 Escort became synonymous with racing and rallying in the Sixties and Seventies, yet perhaps no car was more easily recognisable than the Alan Mann Racing prepared ‘Works’ examples with their ‘bubble’ wheelarches and distinctive red and gold livery. Despite a capacity of just 1.6 litres, the Formula 2 Cosworth FVA engine with its 16 valves and double-overhead cams fitted to the Alan Mann cars generated around 220bhp, driving through a magnesium-cased 2000E gearbox. Underneath, was a specially designed multi-link rear suspension while, up front, the steering rack was enclosed in the engine crossmember. Driven by Frank Gardner and teammate Jackie Oliver, the AMR Escorts dominated the 1968 British Saloon Car Championship, winning it for Ford.

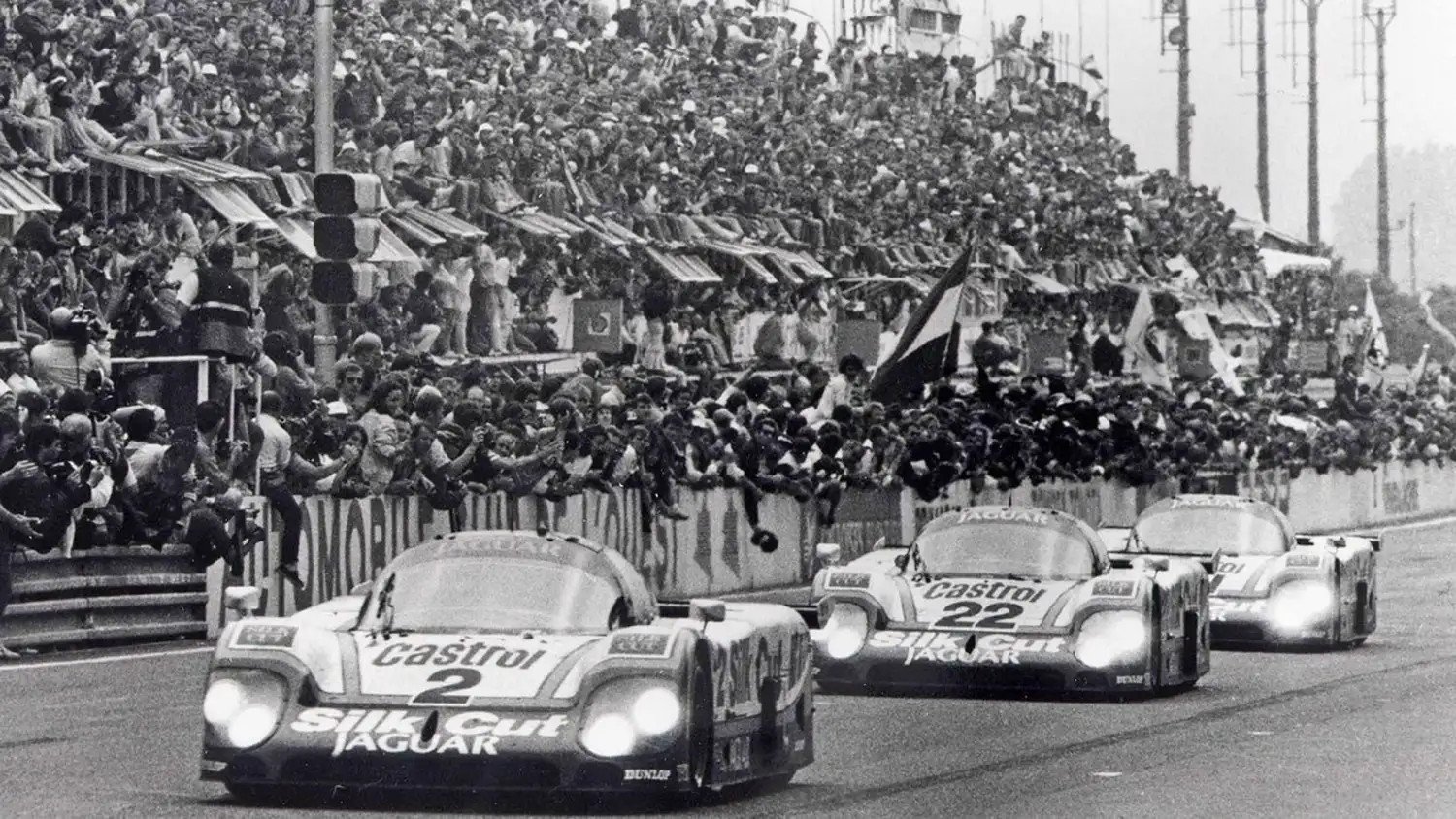

Jaguar’s glory days returned at the 1988 Le Mans, when three XJR-9s such as the one in the Great British Racing class howled over the finish line in first, fourth and 16th positions; the Big Cat’s first win at the circuit since its D-Types romped home in the top four places in 1957. Designed by Tom Walkinshaw Racing, the XJR-9 featured a supremely aerodynamic body allied to a light but rigid carbon-composite construction, and was fitted with a beast of an engine. Fighting for space with the driver was a 6.0-litre Jaguar V12 producing 650bhp – or a colossal 750bhp in 7.0-litre form – good for a top speed of 245mph. It powered the winning car driven by Jan Lammers, Johnny Dumfries and Andy Wallace for 394 laps and 3,313 miles over 24 hours; a tribute to great British engineering.

Andrew Evans, Managing Director, London Concours, said: “The Great British Racing display is a colourful reminder of the proud tradition of British engineering excellence that created some of the legends of motor sport. Cars and drivers alike flew the flag for British ingenuity and can-do attitude during those glory days, and captured the popular imagination in the process. It’s an enduring legacy we need to celebrate.”

“Guests to the HAC will be treated to an unprecedented array of cars, along with a decadent range of food and drink options, and a carefully curated line-up of luxury brands and boutiques. London Concours 2024 is set to be another occasion of total automotive indulgence.”