FORD VS. FERRARI: ENTRY AND FAILURE – 1964

A sparsely worded newswire release was issued on May 22, 1963 noting, “Ford Motor Company and Ferrari wish to indicate, with reference to recent reports of their negotiations toward a possible collaboration that such negotiations have been suspended by mutual agreement.”

The flurry of negotiations between the companies had ended, but Ford’s desire to become a player in performance motorsports remained strong. A month later, the High Performance and Special Models Operation Unit was formed with the mission to design and build “A racing GT car that will have the potential to compete successfully in major road races such as Sebring and Le Mans.” The unit’s resulting work, the GT Program book, circulated internally on June 12th and contained the initial design concepts for the GT40.

The high performance team included Ford’s Roy Lunn, who already developed a preliminary design in the GT Program Book, along with Carroll Shelby and a few other Ford officials. Their first job was to identify a team that could build the cars. As project engineers, they chose Eric Broadley, whose Lola GT was considered groundbreaking, and John Wyer, who had won Le Mans with Carroll Shelby driving for Aston Martin as the race manager. This established a four-pronged team with Lunn and Broadley designing and building the cars, Wyer establishing the race team and Shelby acting as the front man in Europe. With ten months until the 1964 race, a workshop was established in Broadley’s garage in Bromley, south of London. But when established as Ford Advanced Vehicles moved the operations to Slough.

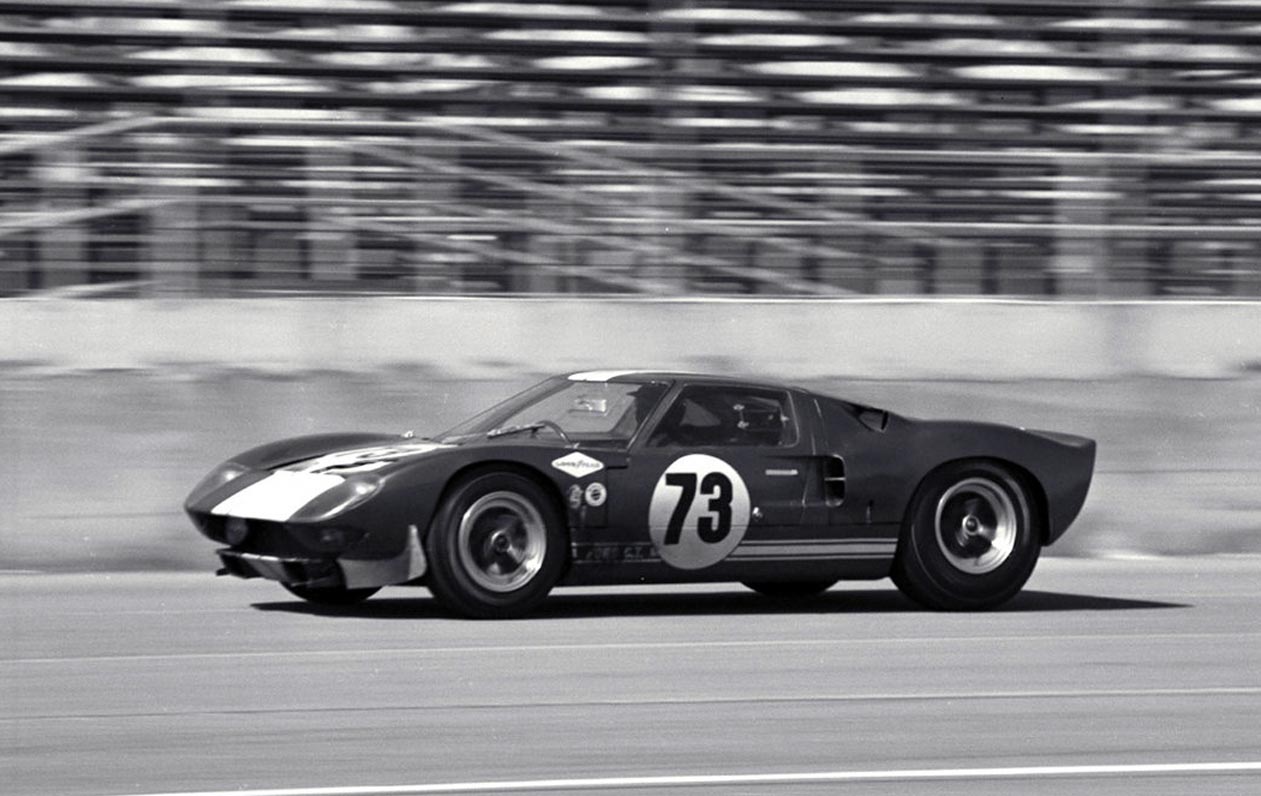

As one of the major design features, Roy Lunn had lowered the two inches from Broadley’s initial Lola to a mere 40 inches and work on the cars began. Interestingly, the first seven produced had a VIN number beginning with Ford GT, while the cars after those had a VIN beginning with Ford GT40. New Zealander Bruce McLaren was the initial test track driver as the car was put through its paces. Early issues with the car were apparent as the Ford Motor Company team tried to accomplish in 10 months what Ferrari had perfected over decades. By April the first car was completed, and was quickly shipped to New York to be used for a press conference prior to the Mustang launch. During the time trials in Le Mans in mid-April, the car’s speed was tremendous, but the aerodynamics needed work as it was difficult to control at high speeds. With McLaren doing the development driving, a spoiler was added and other modifications made. The car was now as ready for racing as it could be for the 1964 season.

Disappointments were soon to follow. While the Ford GT40s were undoubtedly fast, endurance was an issue at all of the races. The suspension let loose in Nuremburg, and while they led for a portion of the race at Le Mans and driver Phil Hill set a lap record, the Colotti gearboxes gave out under the strain of the speed and number of shifts required to complete the loop. All three Ford cars were out of the race 12 hours into the required 24. Further disappointments culminating in a disastrous showing in Nassau in December left the program in shambles, and the decision was made in Dearborn to move the work back to the US, with Carroll Shelby given operational control and Roy Lunn engineering control.

THE 427 GT40X – 1965

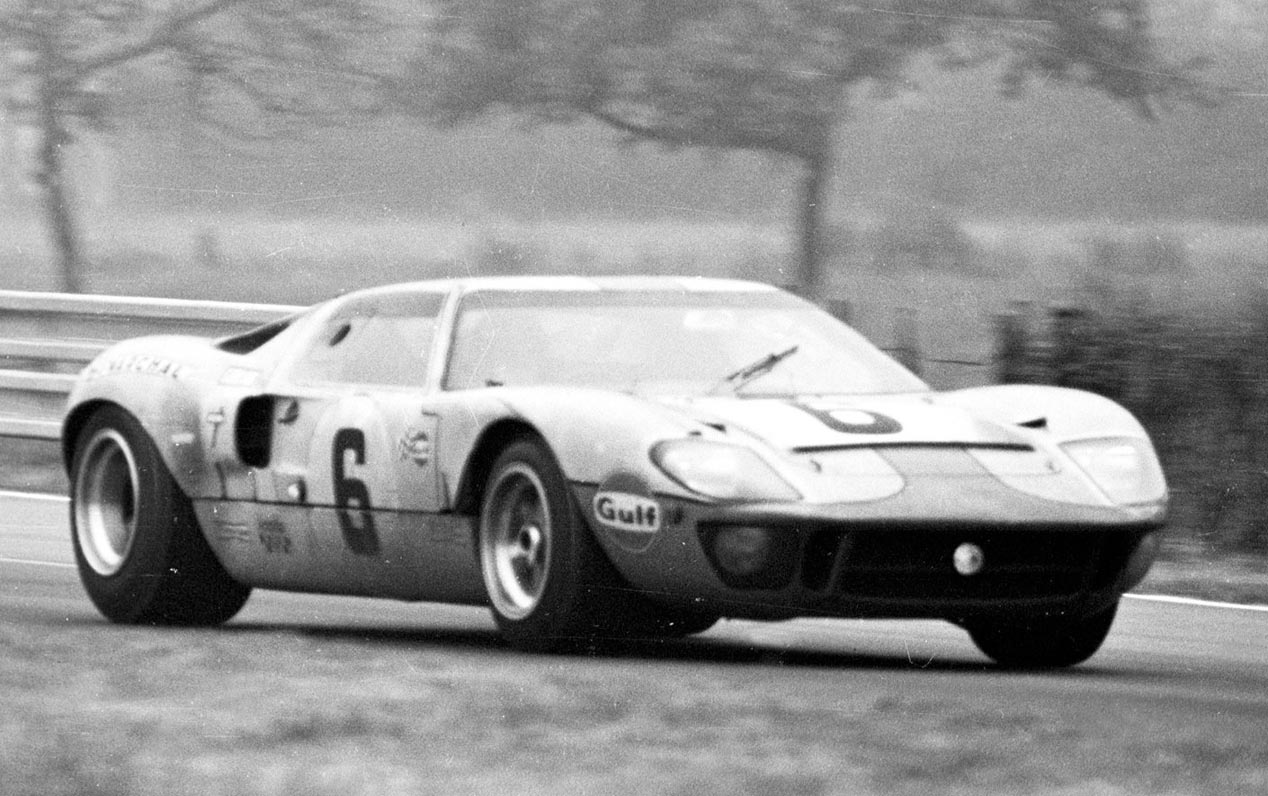

When the remaining cars arrived at Shelby’s workshop in Los Angeles in December, Ken Miles, Shelby’s developmental driver, got to work on them. Miles discovered that the initial design settings had been lost and when he reset the suspension to the original settings, performance increased substantially. The team began to test the aerodynamics with both the aid of a computer installed by Ford Aeroneutronics and the old fashioned way with yarn taped to the cars on both the track and in the Dearborn wind tunnel. They soon discovered that the airflow was worse than had been imagined. They gained up to 79 horsepower as Shelby America engineer Phil Remington rearranged ducting to change airflow. The changes continued as lighter weight fiberglass replaced heavier aluminum and steel, and wider magnesium wheels replaced the wire spoke version along with a hundred other modifications. Suddenly the GT40 began to not only look like a racing car, but to perform like one.

The first race of the year was in Daytona and for the first time, the Fords completed an endurance race taking first and third, with a Shelby Cobra (running a Ford engine) sandwiched in between in second place. The 1965 season had started well – at least the cars were capable of finishing. After a second place showing at Sebring, the cars were shipped to France for testing at Le Mans during the time trial weekend in April. The Ferraris dominated the time trials as the Ford team scrambled to make modifications to the cars, experimenting with different engines and gearboxes.

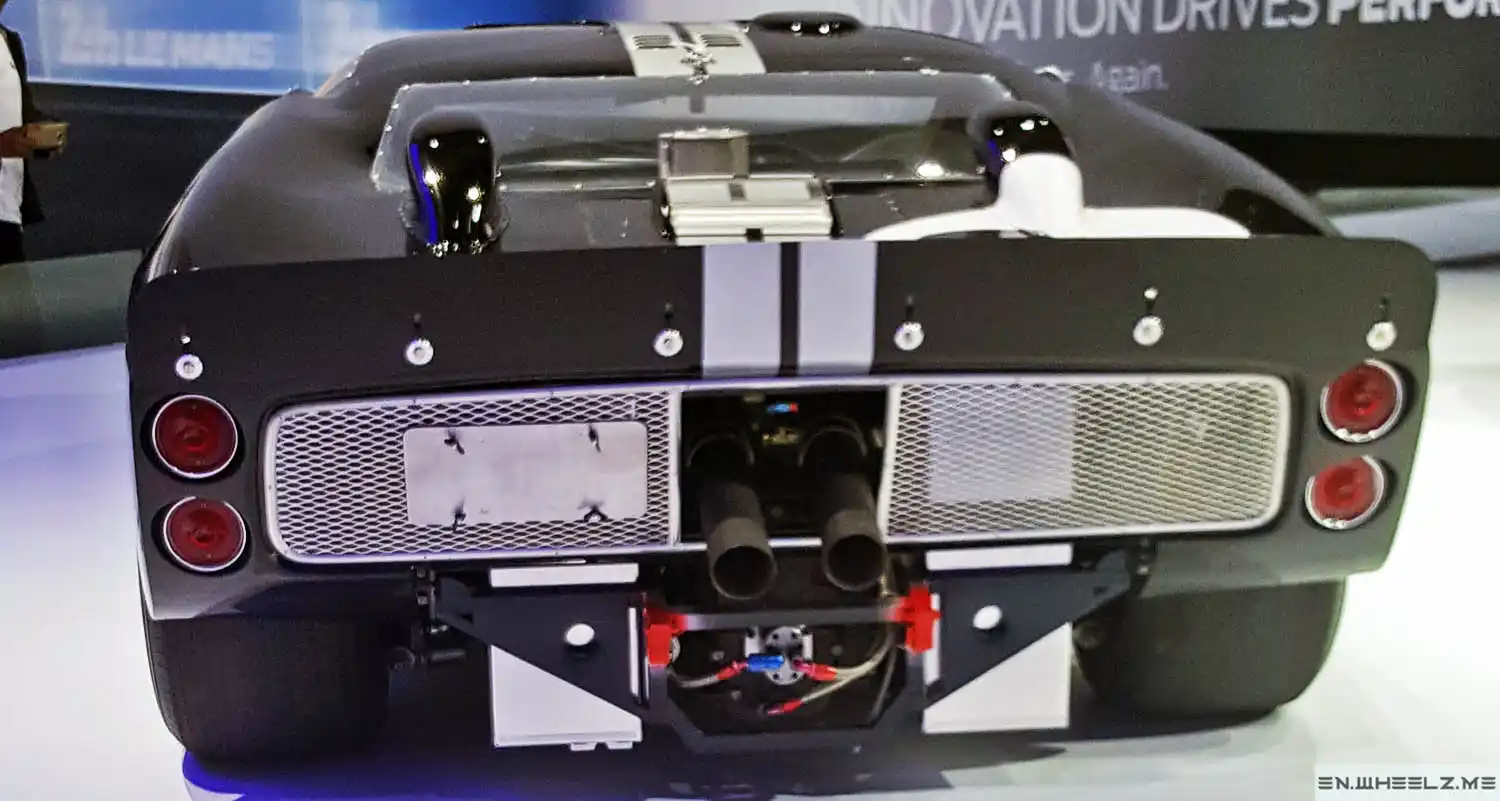

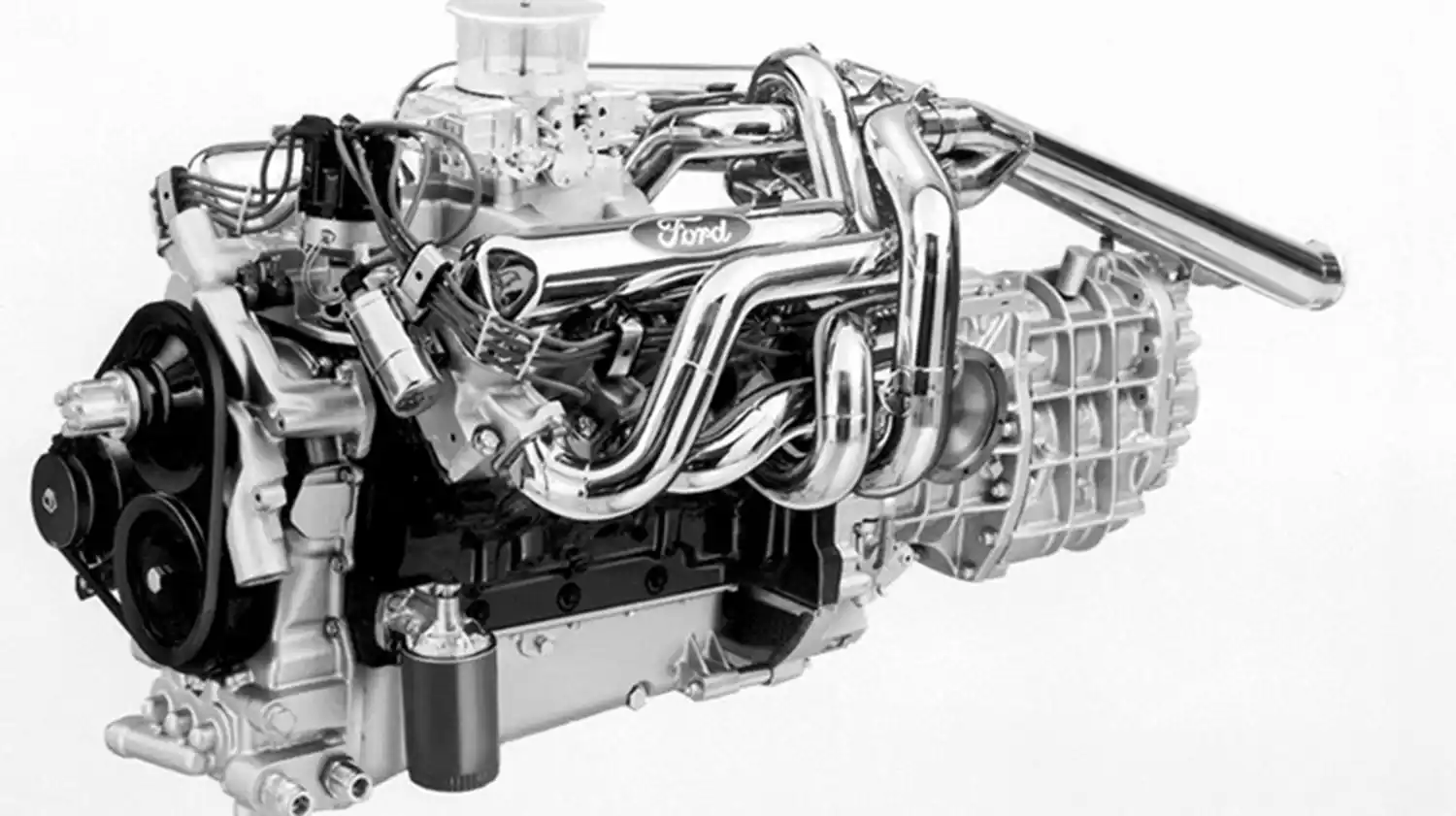

While things did not look good for Le Mans, in Dearborn Roy Lunn and his team had a new version of the GT40 ready for testing. Ford Motor Company had been working to develop and perfect a 7-liter 427 cubic inch engine. Lunn and his team had worked an engineering marvel to fit the larger engine in the mid-engine car while retaining aerodynamic integrity. Ken Miles and Phil Remington flew from Le Mans to Dearborn to test the car at the Romeo test track. Just before lunch, Miles took over the development driving and work continued on the car as spoilers were added and modified, and speeds increased until Miles hit 210 mph on the straight away. When Lunn asked for opinions, Miles said, “That is the car I want to drive at Le Mans this year.”

With only four weeks until the race, the team decided prepare two of the cars with the 427 engine (called the GT40X) and to supplement the team with the existing GTs with the existing 289 engines that were already racing in Europe. During the practice laps, the 427 set the lap record at 3:33, almost five seconds faster than the Ferraris! Ken Miles received his wish as he and Bruce McLaren teamed up to drive one of the GT40X cars. While the Ford had set the lap record, the race was an unmitigated disaster. In the rush to prepare the newer GT40Xs, small mistakes were made in the gearbox (Roy Lunn later said he cost the team the race in rebuilding them just before they were shipped to France.) The team did not know that the new 289 engines were unstable, as the engineering team had been devoting its attention to the Indianapolis 500 engines, sending untested engines to Le Mans. That evening, Leo Beebe called all the teams together and while they expected the worst, Beebe told them it was a “victory meeting! Next year we’re going to come back here and win, and we might as well start now.”

THE LE MANS COMMITTEE – VICTORY IN 1966

One of the first changes made for the 1966 racing season was the establishment of the Le Mans Committee, which was comprised of the heads of a number of Ford divisions involved, including the Engine and Foundry, General Parts, and also expanded the role of the Dearborn Motorsports and Styling and Engineering teams. By doing so, the Committee was able to slash through the vast amounts of red tape, which had hindered the program to date.

Additionally, Ford Motor Company decided to bring on its NASCAR racing team Holman & Moody in addition to Shelby American. The Committee established a monthly meeting cadence with extensive preparation and John Cowley was placed in charge of the day-to-day operations of the GT Program, with Homer Perry named day-to-day liaison to Shelby American and Holman & Moody.

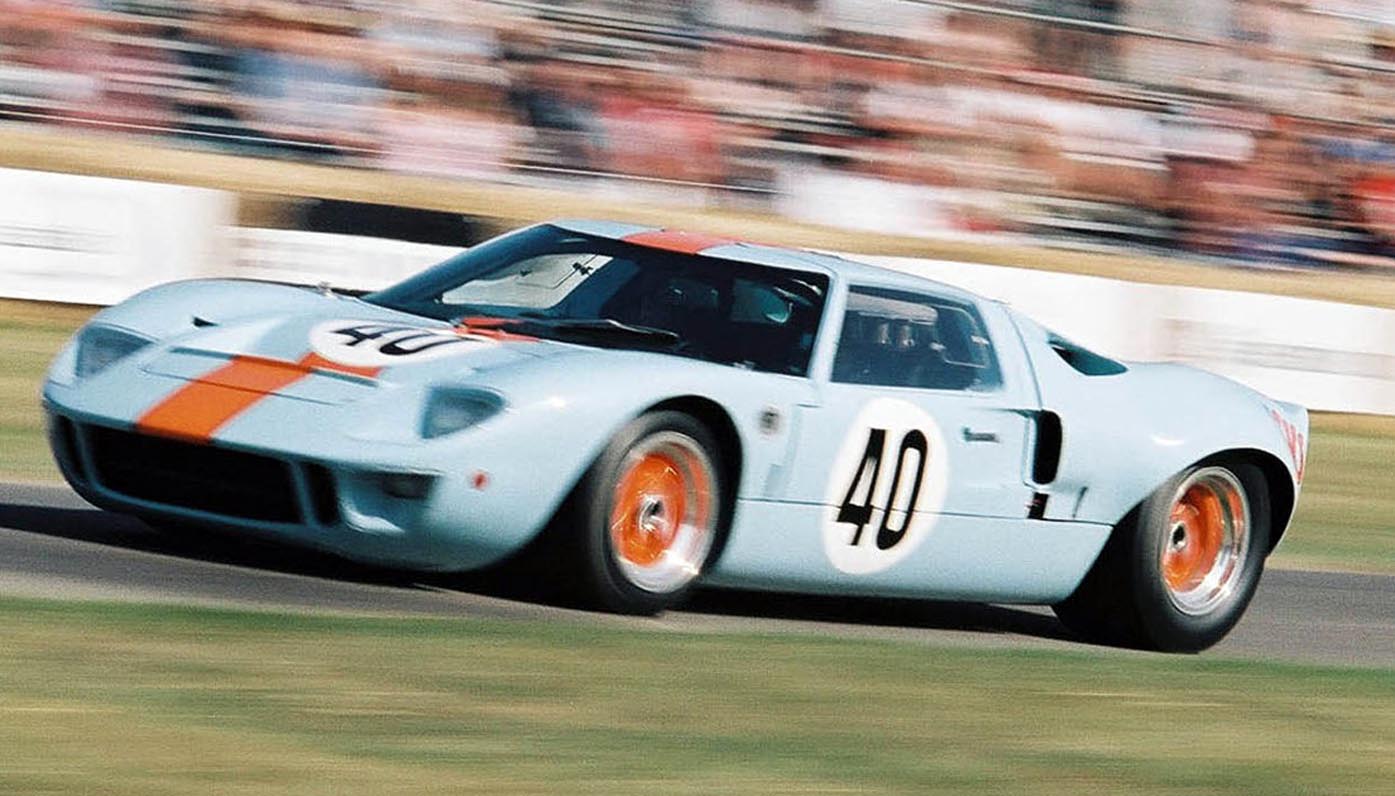

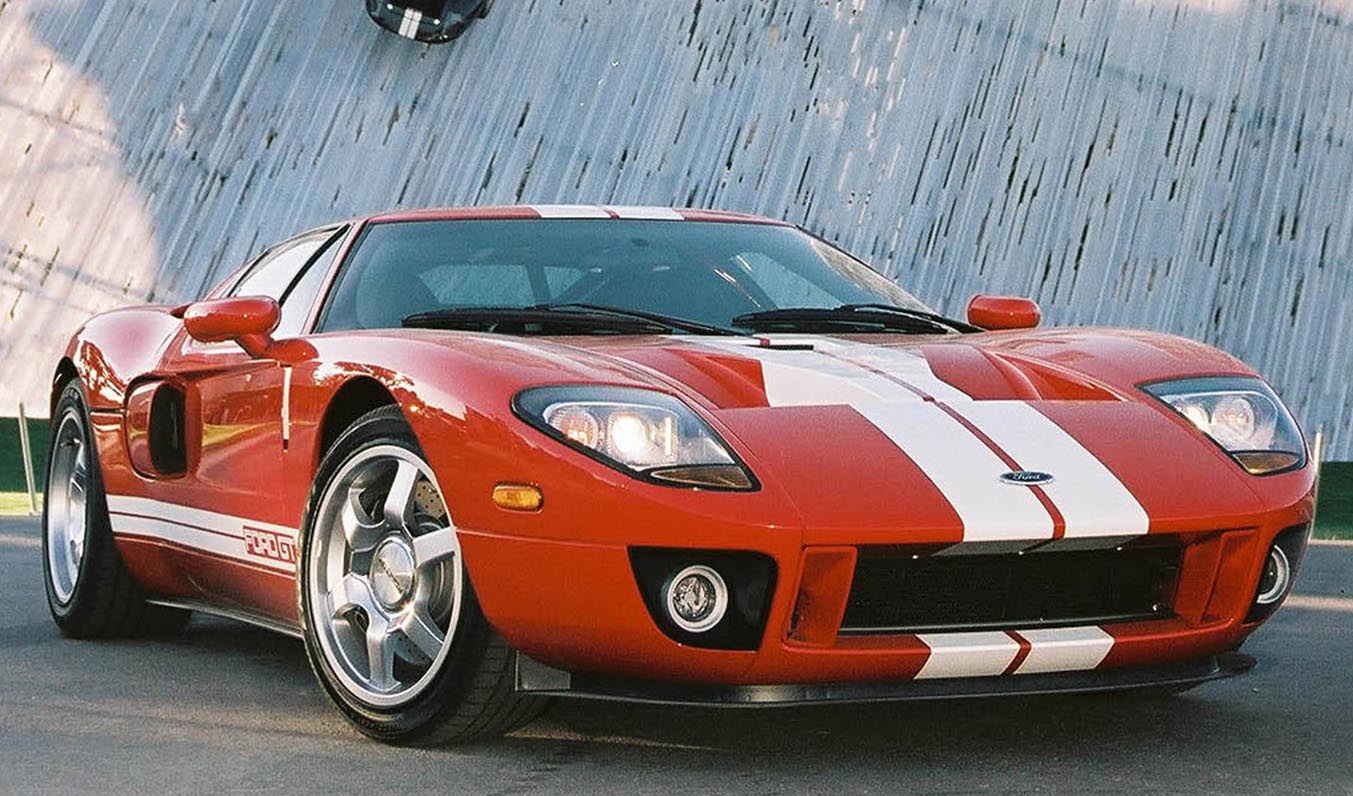

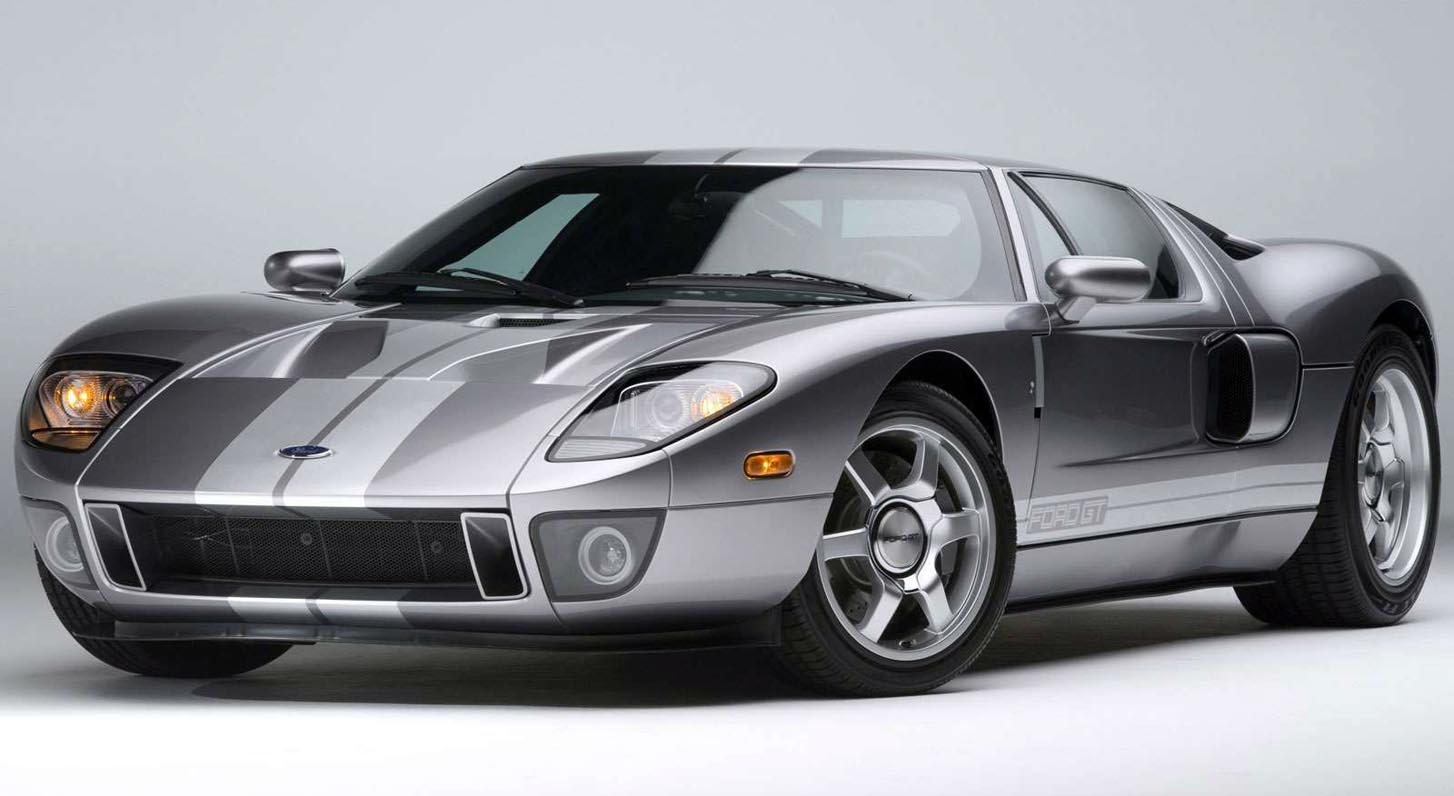

With time and resources now fully available to the Le Mans Committee, the perfect partnership of Ford Engineering, and the racing acumen of Shelby and Holman & Moody, combined to fully develop the 427 GT40. Phil Hill and Ken Miles continued to race and modify the car, and by mid-September had made enough changes to the body, suspension, fuel system, and brakes that the new model, now designated the Mark II, was ready for testing in the Dearborn wind tunnel. One of the changes was to use heavier gauge metal, which increased weight and stress on the brakes. Ken Miles continued testing a short-nosed body style which added eight mph to the car. The team finally felt that they had a winning car, with the brakes and gearbox the biggest concerns. Interestingly, the Mark IIs only used four speed manual transmissions, as the bigger engine put out so much torque that a five-speed gear box was considered unnecessary.

The initial race of the year was in February at Daytona, which was increased from 12 hours to 24 hours. Ford fielded five teams, three under Shelby and two under Holman & Moody, including an experimental automatic transmission. Ferrari did not enter any of their factory cars and the race was over within an hour of the start, as the leading competition fell out of the race. The Ken Miles/Lloyd Ruby team led from the beginning and were easily the winner, with Ford sweeping the first three places.

Next on the schedule was the endurance race at Sebring. There had been discussions among the Le Mans Committee whether the heavier more powerful Mark IIs were better than the lighter 289 GT40s on a course that required more agility and maneuverability, so a selection of the two were entered under the Shelby American, Holman & Moody, and Alan Mann racing banners. This time, Ferrari entered one of its factory 330P3 cars driven by a team including the great Mike Parkes. Over the course of the night, it became apparent that the two lighter 289 GT40s did not have the topline speed to keep up with the Ferrari, while the Mark IIs piloted by Ken Miles and Dan Gurney cruised along, keeping pace. Whereas Ken Miles had been given permission for the quicker lap time in Daytona, during the team meeting prior to the Sebring, Dan Gurney had been given the faster lap time with Miles to run two seconds slower.

The Ferrari transmission began to give out in the 7th hour and eventually was forced to retire. With the last of the major competition out of the race, the slow down signal went out to Gurney and Miles – and was ignored by Ken Miles as he continued to push the car in a private race with Dan Gurney. Eventually, Carroll Shelby climbed on a block and waved a hammer at Ken Miles, who finally obeyed the signal to slow down to spare the cars and ensure they finished. That lack of team play would come back to haunt Ken Miles.

With the slowdown in place, Gurney built a lead of a lap on Miles and was cruising along to victory until the unthinkable happened. The engine threw a rod with the car rolling to a stop a mere hundred yards from the finish line. Gurney was not quite sure what to do when a minor official told him he could push the car across the finish line. Unfortunately for Gurney, he was instant disqualification as drivers are not allowed to push their cars unless pushing them off the track for safety reasons. Ken Miles was awarded the victory, his second of the season, as Ford once again swept the first three places on the podium.

The issue with Dan Gurney’s engine proved to be a blessing in disguise, as the Ford Engine and Foundry team stripped the engine down to examine all of the components to see if it could be improved. Ken Miles assisted the team by developing a dynamometer “tape” of Le Mans, so the engines could be tested under race conditions. This tape allowed the team in Ford’s test block 17D to attempt to perfect an engine that could run for up to 48 hours, twice as long as the race itself. Ford Engineer Gus Gussel noted that with the dyno tape created “it was like Ken Miles was in that control room running that car.” Learn more about the dyno tape in the historic video in the last tab of this story. Finally, by the end of May, an engine producing 6,400 RPM and 485 horsepower was consistently lasting the desired 48 hours. They then built 12 of them to specifications of the test engine and shipped them to Shelby American, Holman & Moody, and Alan Mann Racing for the Le Mans cars.

The other major engineering obstacle was the brakes. With the increased weight and speed of the Mark II cars, the brakes took a beating on each circuit. Slowing from speeds of more than 200 mph into a hairpin curve would cause enough heat to boil the brake fluid, warp the rotors and crack the brake pads. Gradually, in experimentation with Ford and Kelsey-Hayes engineers, better materials were sources for the pads and rotors. A story that circulated among the teams was that one of the foundries could not produce enough material for the pads, so Ford Motor Company purchased them to ensure all necessary materials would be delivered. With a true team effort, Phil Remington of Shelby American developed a quick change system for the calipers and John Holman built a quick change setup for the rotors, so even if there were issues, the brakes could be changed out in mere minutes.

Finally June arrived, and a virtual army of Ford Engineers descended on Le Mans to support the armada of Ford Motor Company cars. One of those was Mose Nowland who said, “the atmosphere was electrified instantly, because we knew the assignment was very important to Mr. Ford. It was just carte blanche for us. The hours of work, the materials required, the places to be, and so on. We knew the mission was important, from the very get-go.” Eight factory cars were entered, three each from Shelby and Holman & Moody, with two more supplied from England by Alan Mann Racing. The main competition would come from 11 Ferraris, which included three 330P3s and four 385P2s.

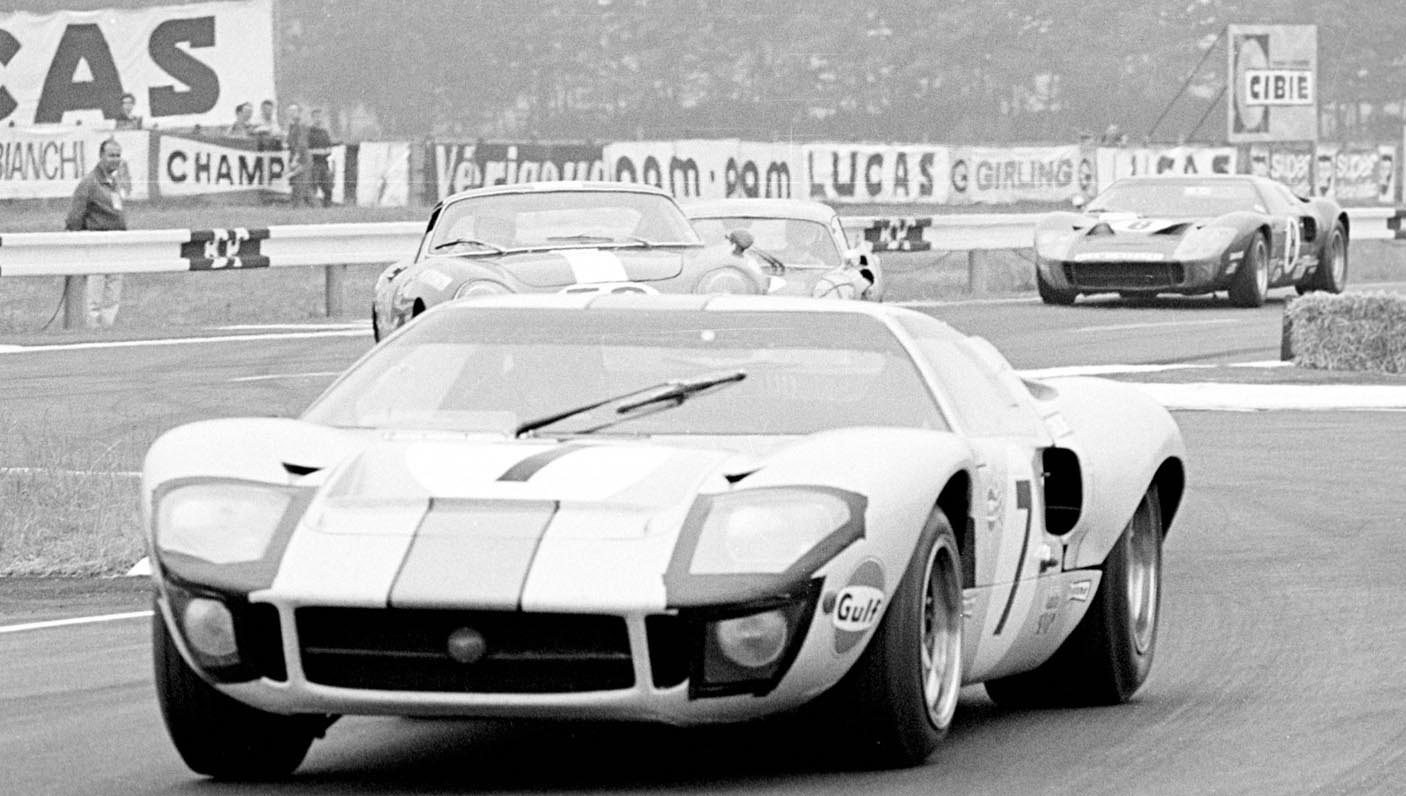

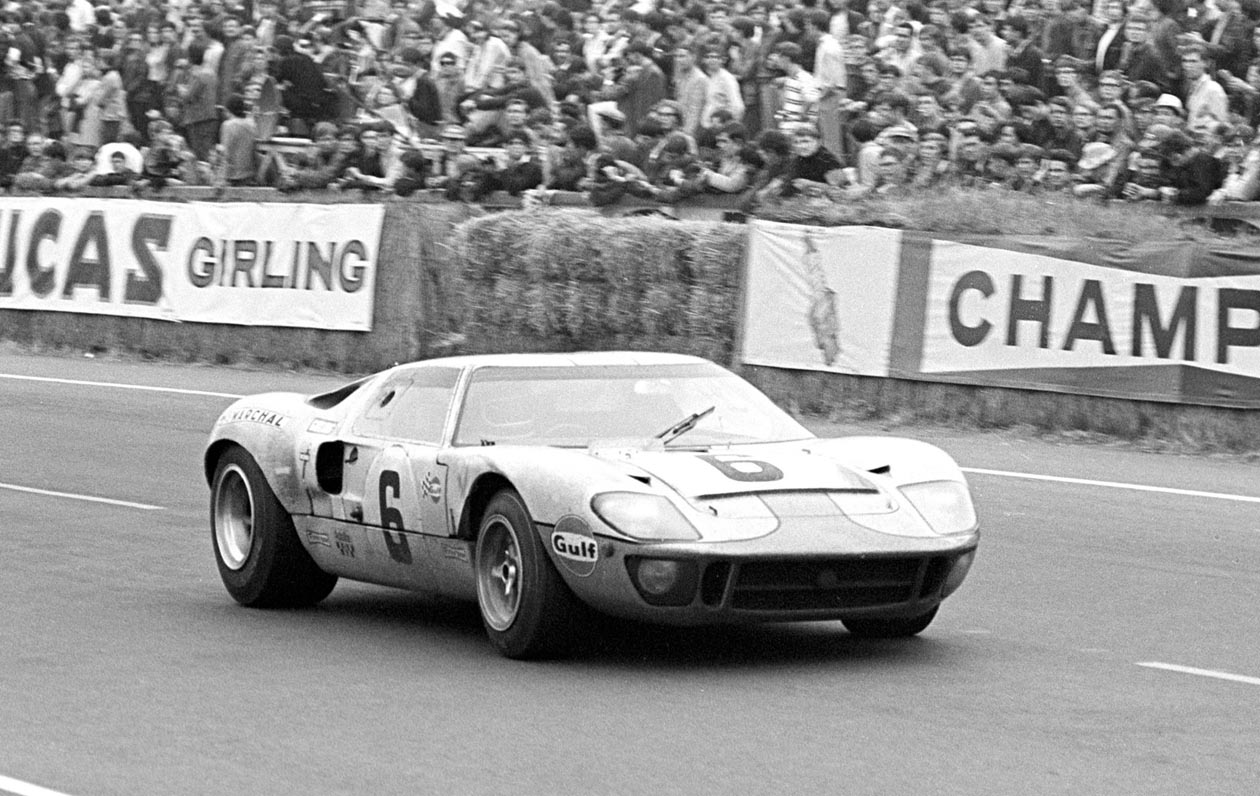

As the day of the race drew closer, the Ford Le Mans Committee arrived to support the team. Henry Ford II had been named honorary chairman of the race and would serve as starter with his wife and son Edsel with him in tow. As the clock hit 4:00 PM on June 18th, Henry Ford II waved the starter flag and the drivers ran across the track to start their cars and the race. Ken Miles, who had the second fastest qualifying time after Gurney, had immediate issues as the door struck his helmet and he had to quickly pit for repairs. The rest of the cars roared on with the Fords and Ferraris trading the lead through much of the early race. The crowds watched knowing that the Fords had often been the fastest cars but never completed the endurance race.

After midnight, the tables began to turn. The Ferraris began to drop out with mechanical difficulties and while Ford had some withdrawals, the bulk of the team raced on and at one point held the 1-2-3-5-8 spots. By 4:00 AM, the last of the Ferraris was out of the race and the order went out for the teams to slow the pace to ensure the most cars could complete the race. The drivers slowed from the early pace of 3:30 per lap to a more strategic 3:50 per lap. Dan Gurney was in the lead most of the evening, with the Ken Miles and Bruce McLaren teams trading 2nd and 3rd place depending upon their pit stop order. When Gurney’s car went out with engine problems around 10:00AM, Ford still had the first three places between the Shelby American and Holman Moody teams.

With two hours left in the race, Leo Beebe and Carroll Shelby met to discuss the end of the race. With the Ford cars running 1-2-3, there was little question as to winning the race, but what order should the finish take? If Miles and McLaren continued their personal race, a malfunction such as the one Dan Gurney had at Sebring might occur. The team also discussed having the cars come across in a tie and inquired of the ACO (Le Mans race organizing committee) if that was permitted. The ACO agreed that this was possible and so the drivers (at this time Ken Miles and Bruce McLaren) were told the news at their next pit stop. While neither was thrilled with the decision, both acquiesced with Ken Miles saying “I work for the Ford Motor Company… if they want me to win the race, why, I’ll do it… and if they ask me to jump in a lake, why I’ll guess I will have to do that as well.”

Miles (who had just taken the lead during a McLaren pit stop) and McLaren began to slow down to allow the third car, driven by the Holman & Moody driver Dick Hutcherson to catch up. By this time, word had come back from the ACO that a tie would in fact not be permitted and since the Bruce McLaren team had started 8 meters further back from the start line it would have traveled further and would be declared the winner. The ACO ruling is a matter of some debate as there was nothing written in the sporting regulations from that year that accounted for the rules in the event of a tie.

The decision to notify the drivers of the change in ACO policy rested with Leo Beebe and Carroll Shelby. As the two conferred, there were a number of considerations. While Ken Miles had done the bulk of the race prep work on the Mark II to prepare it for competition since his first drive in February, 1965, Bruce McLaren had been with the program since its inception in 1963 and had always been a true team player driving at the assigned speed. Both drivers felt they could win in a race to the finish as neither had more than a lap or two lead during the second half of the race. Leo Beebe ultimately made the decision to not notify the drivers and let the dead heat occur, which would make the McLaren team the victor. Beebe later noted that “to have Ken win would have been more expedient and popular, but the extent to which McLaren and Amon had played exactly according to our rules mitigated against Miles. The result was not necessarily even popular with me.” Ultimately, Beebe felt that Ken Miles trying to push the Dan Gurney car at Sebring was a big enough strike against him to give the nod to the McLaren/Amon team.

During the final lap, the three Ford cars rode in tandem with Miles and McLaren crossing the finish line in a dead heat with Hutcherson close behind in 3rd place. Photos at the time appear to show McLaren surging ahead at the final moment, but the checkered flag is actually waved some distance from the final finish line, which was being monitored by newly installed IBM electronic time keeping devices. The photo finish was intact. As the cars approached the victory circle, Ken Miles and fellow driver Denny Hulme who hanging out of the passenger side door, were surprised when they were waved off to allow McLaren and Amon to the victory podium. Both were crestfallen when they learned of the changed ACO rule interpretation, but Ken Miles had the most to lose. He would have been the first driver to win Daytona, Sebring and Le Mans in the same year. In an interview a few months after the race he was philosophical, noting once again that he worked for Ford and would accept whatever outcome occurred.

This victory was a culmination of three years of engineering, design, and research to develop a winning car and winning team. Motorsport racing requires a combination of engineering, artistry and intuition from the drivers. With the Mark II all three elements were in play. Ford Motor Company engineering did tremendous work on the elements of the car and many were highlighted in papers to the Society of Automotive Engineers, while the stellar teams of Shelby American and Holman & Moody provided the artistry to turn the cars into unbeatable racing machines, and the drivers provided the vision and courage to navigate the difficult courses. For the Ford Engineers like Mose Nowland, it was the culmination of years of hard work. He described the scene in the Ford pit area when they knew the race was won. “There was a lot of tears, a lot of joy. There wasn’t a lot of glad-handing in those days. But I think the most rewarding thing that day was the smile on Mr. Ford’s face because he so dearly wanted to win that race. You just felt that you had made a very fine contribution, because there’s that gentleman, and he was very satisfied. For us who worked on it, there was a glow that lasted for weeks, and now all these years.”

Three years after being rejected by Ferrari, Ford Motor Company had developed one of the best endurance cars in the world and won on the field of contest. With the LeMans victory, Ford Motor Company won the Manufacturer Championship because of their combined scores. The 289 GT40 also won the Sports 50 (at least 50 street versions produced) title for Ford as well.