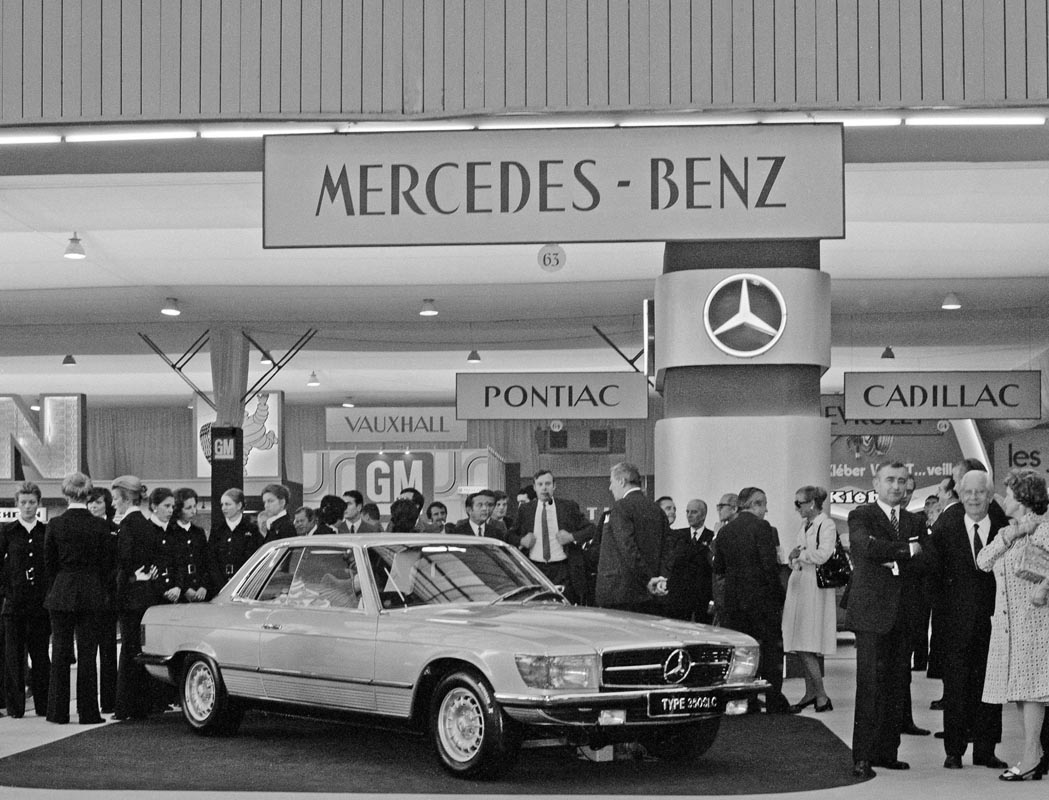

It was a glamorous premiere: in October 1971, Mercedes-Benz presented the SLC Coupé at the Paris Motor Show, a popular stage for elegant creations. The four-seater vehicle combined dynamic driving performance with maximum driving comfort and was – for instance – perfect for long-distance journeys.

The first model to be showcased at the exhibition in the French capital was the 350 SLC. Additional models followed and the brand even celebrated motorsport success with the 450 SLC 5.0 and 500 SLC evolution stages: Mercedes-Benz works teams raced in endurance rallies, claiming overall titles in both South America and Africa. Well-cared-for models of this SLC model series have long since become sought-after classics with a potential to gain further value.

Decision to cut corners: On 18 June 1968, the Board of Management decided in favour of launching the series production of the new SL (R 107) as a successor to the W 113 “Pagoda” model series. At this point, discussions were still ongoing about whether the W 111 model series coupé was also to be succeeded.

One option would have been to wait for the new 116 model series S-Class as the technological basis – given it was just being developed at the time to ultimately be launched in September 1972. However, development capacities would have meant it would have only been possible to complete the new coupé in the mid-1970s.

The decision to base the coupé on the SL was made to cut the model’s time to market – and that came thanks to the body construction department in Sindelfingen: the team headed up by Karl Wilfert initially unofficially developed a coupé variant of the R 107 and showcased it to the Board of Management as a “rough cut”.

The Board of Management grabbed the bull by the horns and consequently the brand introduced the C 107 luxury coupé in October 1971, thus only six months after the world premiere of the new SL. Series production launched in April 1972, lasting until 1981, with a total of 62,888 vehicles built during this time.

The 450 SLC was the most popular variant with 31,739 units. Successors were – once again – the large C 126 Coupés based on the S-Class model series. The R 107 model series SL remained part of the range for significantly longer than the SLC Coupés: it rolled off the production line until 1989.

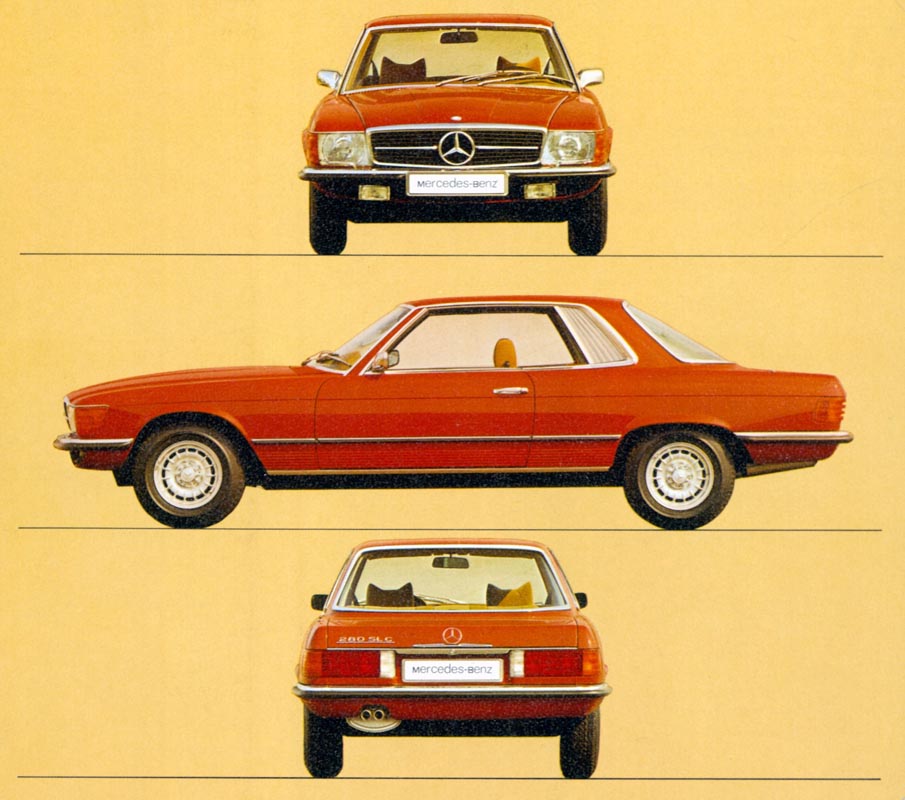

Identical front section: The SL and SLC were identical from the front end to the windscreen. From then on, the coupé grew taller and longer. From the side, the four-seater’s longer wheelbase became immediately obvious as it was a considerable 360 millimetres longer with a total of 2,820 millimetres.

The flat roof towering over the passenger compartment transitioned into a fairly tilted rear window that was curved in two directions. Compared with the SL, the boot lid was also slightly curved in two directions.

As is the case for all the brand’s large coupés, the side windows were fully retractable without the interfering B-pillar, thus lending the SLC a particularly elegant look. However, the tight gap between the stretched doors and the rear wheel arches meant there was only little space to fully retract the rear side windows. For this reason, they were split into two sections with the smaller segment featuring louvres.

Safety first: As a result of tighter safety stipulations – most of all in the US – the roadster already featured stronger A-pillars. As a result, the SL was awarded homologation in the US even without the “Targa” bar. The SLC benefited from this design.

Its safety body also consisted of a floor assembly made up of sheets with different thicknesses to lend the vehicle the predicted crumple behaviour. The fuel tank had been positioned in front of the rear axle to protect it from collisions. The new, four-spoke steering wheel featuring an impact absorber was wrapped in polyurethane foam.

The coupé weighed around 50 kilograms more than the corresponding roadster. Both variants’ driving performance was almost identical as a result of the SLC’s drag coefficient of 0.423 (1973) being lower than the SL’s value with a hard top (drag coefficient = 0.489).

V8 as the power source: The technology in the roadster and coupé was very similar. The 3.5-litre engine (M 116) initially available in both model series had previously already proven its worth in the W 108 and W 109 model series saloons as well as in the W 111 model series coupé and cabriolet variants.

It generated 147 kW (200 hp) and propelled the 350 SLC from 0 to 100 km/h in nine seconds and on to a top speed of 210 km/h. The 450 SLC featuring the M 117 engine and 165 kW (225 hp) followed in 1972, with the 280 SLC featuring a six-cylinder 2.8-litre engine and 136 kW (185 hp) being added to the range a year later. In September 1977, Mercedes-Benz launched the 450 SLC 5.0 generating 177 kW (240 hp).

The top-of-the-range model featured a subtle front spoiler and a black plastic rear spoiler. Bonnet, boot lid and bumper reinforcement were made of aluminium. More stringent emissions standards – also in Europe – led to modified injection systems and consequently a slightly varying engine output. The 380 SLC and 500 SLC were only available in the last year of production.

The chassis and suspension of roadster and coupé were based on the cutting-edge designs of the “Stroke Eight” executive category models. In 1980, the three-speed automatic torque converter transmission was replaced by a four-speed variant while the basic variant of the 280 SLC was equipped with a five-speed manual transmission.

The SLC in motorsport: Between the post-war Silver Arrow era in 1954/1955 and the return to circuit races as official works entry with the World Sportscar Championship and German Touring Car Championship (DTM) in 1988, Mercedes-Benz took part in rallies with a works team from 1977 to 1980.

It all started with the rally from London to Sydney. A team headed up by engineer Erich Waxenberger was responsible for six largely standard 123 model series 280 E Saloons. The engine (M 110) generating 136 kW (185 hp) was identical to the variant in the 280 SLC. After more than 30,000 kilometres, four Mercedes-Benz drivers finished in first, second, sixth and eighth place. Andrew Cowan’s team claimed top spot.

Waxenberger was aware of an even more successful model for endurance races – the 450 SLC 5.0. The brand signed up four SLC Coupés and two 280 Es for the Vuelta à la América del Sud mammoth rally from 17 August to 24 September. After 30,000 kilometres in 42 days through ten South American states, Andrew Cowan was once again crowned the winner.

The other Mercedes-Benz vehicles followed in second, third, fourth, sixth and ninth place. At the East African Safari – an event deeply steeped in tradition – Hannu Mikkola and his 450 SLC 5.0 led the field for a long time, ultimately finishing as runners-up. At the end of the year, four SLC Coupés completed a one-two-three-four victory at the Ivory Coast Rally with Mikkola claiming the title.

At the 1980 Safari Rally, material defects on the rear axle stopped the teams from fighting for the title, yet Vic Preston Jr was still able to finish in third place. At the end of Bandama Rally, the revamped Ivory Coast Rally, the 500 SLC rally vehicles scored a one-two finish.

Today, the winning car, driven by Björn Waldegård and Hans Thorszelius, is on show at the Mercedes-Benz Museum. Mercedes-Benz withdrew from rally racing before the 1981 season. Privately funded driver Albert Pfuhl bought all the material, consisting of six 500 SLCs, spare parts and 600 tyres.

Teams made up of Albert Pfuhl and Hans Schuller as well as Jochen Mass and Stephen Perry finished 44th and 62nd respectively at the 1984 Paris–Dakar at the wheel of two of these vehicles. Finally, touring car sport: Clemens Schickentanz and Jörg Denzel won the touring car Grand Prix on the “Nordschleife” circuit of the Nürburgring in 1980 with the 276 kW (375 hp) Mercedes-Benz 450 SLC AMG. The sensational coupé with an infernal sound had fulfilled its mandate after two years of development not only to generate technical know-how for road vehicles, but also to win.